Their finest hour...

Flying Officer John Fleming MBE (1915-1995)

The Battle of Britain, the first major military campaign fought entirely by air forces, had been raging since July, however, the night of September 7th and 8th 1940 saw London experience its first constant day and night attack. This relentless bombing campaign lasted for 56 nights and came to be known as The Blitz. By the morning of 8th September, the devastation was clear; railway lines had been disabled, warehouses were burning, whole streets flattened, and hundreds of lives lost.

RAF squadrons were scrambled to intercept the enemy on their inevitable, dreaded, return – amongst them was 605 Squadron Croydon with John Fleming in one of the Hurricanes . After intense aerial combat, the enemy Messerschmitt BF109 and Dornier Do17 bombers turned back, giving Londoners a brief respite before the Luftwaffe returned again that night. However, not all Allied fighters made it back to base.

Fleming was a Scottish-born New Zealander whose university education permitted a direct-entry permanent commission in the RAF. He set sail for the UK on 6th May 1939 and began his flying training the following month. By the time war was declared against Nazi Germany upon their invasion of Poland at the start of September, Fleming had completed his training and joined 605 Squadron.

On the morning of 8th September, Fleming and his squadron set off over Tunbridge Wells to face the enemy bombers. His aeroplane was shot down in flames during the conflict but Fleming managed to bale out, making a drop of 20,000 feet.

He was found, extremely badly burnt, and taken to a local hospital before being transferred to RAF Hospital Halton, where he was considered a hopeless case after refusing a double leg amputation. Thankfully, he was found by a surgeon who had been appointed consultant in plastic surgery to the Royal Air Force, and moved to the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead. Under the leadership of that certain surgeon, fellow New Zealander Sir Archibald McIndoe, this hospital had become a specialist burns unit and was pioneering reconstructive surgery. Unfortunately, Fleming was considered too damaged for plastic surgery, but the forward-thinking McIndoe suggested they try a still largely experimental saline bath treatment. What did Fleming have to lose?

Within weeks of starting the treatment, tiny dots of skin began to grow.

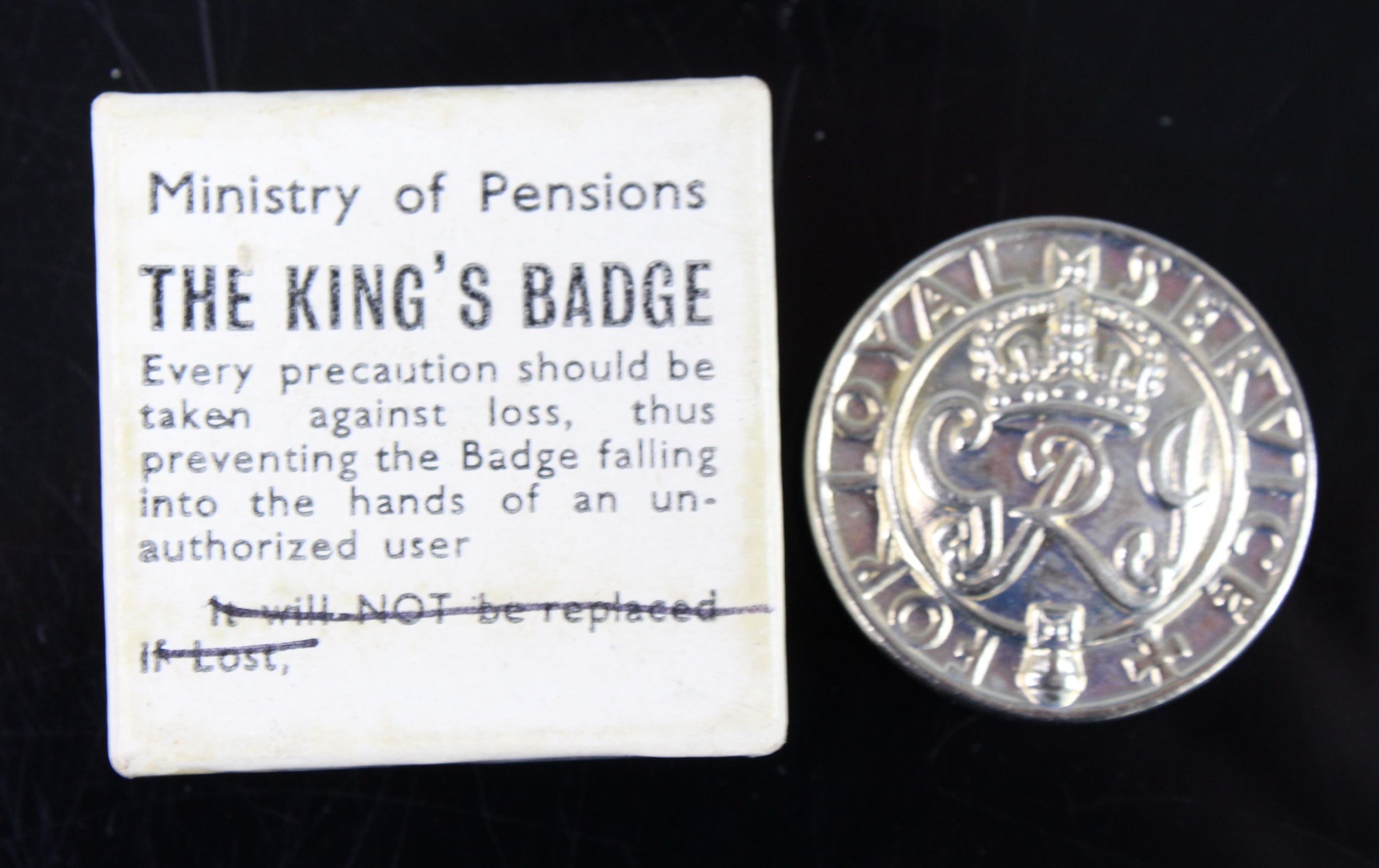

Some of McIndoe’s patients went on to form the Guinea Pig Club in 1941 for aircrew who had undergone his experimental treatments. With just 39 patients, including Fleming, at the start, the club had 649 members by the end of the war. This wasn’t the only club which Fleming’s catastrophe had earned him entry into. Amongst this collection of medals is an amethyst-eyed (silk-worm) caterpillar awarded to people who have successfully used a parachute to bail out of a disabled aircraft.

By August 1941, Fleming was discharged and resumed his duties with the RAF as Chief Armament Officer for Operational Training Units before moving on to be Inspector of Bombing & Gunnery and tracking V1 and V2 sites as the Allies finally advanced into formally enemy-held territories.

He was awarded the MBE in 1944 and continued in the RAF until retiring in 1959. Fleming settled in the UK, where he stayed until his death in 1995.

The medal group comprises the yellow metal Caterpillar Club pin badge, having amethyst set eyes and pin fitting engraved verso 'P/O J. Fleming Pres. By. Irvin Co', 19mm; a group of six miniature medals mounted for wear to include an M.B.E. 1939-1945 Star with Battle of Britain clasp, Air Crew Europe Star, Defence, War with oak leaves and E.R. II 1953 Coronation medal; and a matching set of six miniature medals mounted on a cloth covered card panel and a boxed King's Badge.

The medal group comprises the yellow metal Caterpillar Club pin badge, having amethyst set eyes and pin fitting engraved verso 'P/O J. Fleming Pres. By. Irvin Co', 19mm; a group of six miniature medals mounted for wear to include an M.B.E. 1939-1945 Star with Battle of Britain clasp, Air Crew Europe Star, Defence, War with oak leaves and E.R. II 1953 Coronation medal; and a matching set of six miniature medals mounted on a cloth covered card panel and a boxed King's Badge.

As with all medals, this group tells an incredible story of courage and resilience, but what Fleming underwent in Britain’s darkest hour and beyond is worthy of continued remembrance.

The Medals & Militaria auction will take place on Friday 8th December, with viewing on Thursday 10am-7pm.